Background

Wetlands provide valuable ecosystem services such as filtration of pollutants, flood regulation, and wildlife habitat. Despite their obvious benefits to humans and wildlife alike, wetlands in the United States have been reduced to less than half of their original area. In California, this is no exception with a loss of more than 91% of the original wetlands. The majority of remaining wetlands is located inland and includes vernal pools, marshes, and wet meadows. These types of wetlands are considered palustrine (marsh-like) emergent persistent wetlands and characterized by herbaceous, not woody, plants. The Wetland Project focuses on these vulnerable wetlands in the Sierra Nevada Foothills where most are found on private land.

While most of the wetlands we study are fed by irrigation water, many natural wetlands are still present. Wetlands are usually found where the land creates a natural depression that allows water to collect and keeps the soil saturated. Natural wetlands may be replenished by groundwater and springs or by precipitation. Precipitation from October to March and snowmelt runoff from April to September add to the water table while evaporation removes from the water table. Irrigation can supplement spring-fed wetlands thereby lengthening their wet period and can create new wetlands in land depressions and on slopes.

While most of the wetlands we study are fed by irrigation water, many natural wetlands are still present. Wetlands are usually found where the land creates a natural depression that allows water to collect and keeps the soil saturated. Natural wetlands may be replenished by groundwater and springs or by precipitation. Precipitation from October to March and snowmelt runoff from April to September add to the water table while evaporation removes from the water table. Irrigation can supplement spring-fed wetlands thereby lengthening their wet period and can create new wetlands in land depressions and on slopes.

In the Sierra Nevada Foothills, ranching and other agricultural practices are very common. Water division has been an important part of life since the Gold Rush in the 19th century. The irrigation system is vital to the livelihood of many people as well as to the persistence of rare wetland habitat. More than two-thirds of the wetlands identified in the Sierra Foothills are fed by irrigation water. Wetlands may be lost by way of land conversion or water diversion or may be created or enlarged by increased irrigation to a site used for grazing. The Wetland Project aims to explore the dynamic relationship between ranching and wetland persistence.

A working landscape is one where market and non-market ecosystem services are produced. This may include livestock, timber, and hunting, as well as wildlife habitat, recreation opportunities, scenic values, and clean drinking water. In the foothills of the Sierra, irrigated pasture and stock water developments are a common part of the livestock grazing that takes place on most of the open lands and is the main economic activity on grasslands and woodlands. Excess water from pastures, natural springs, or leaks from stockponds, may create a palustrine emergent wetland that is then used by wetland species including a small secretive bird known as the California Black Rail.

These small wetlands add important habitat diversity and provide water for a variety of plant, animal, and insect species. Livestock may occasionally also find them a source of green forage when surrounding rangelands are dry or lacking green grass. Recent research in California has shown that forest and rangeland owners of parcels of all sizes value wildlife habitat on their lands and are active in maintaining and improving it (Ferranto et al. 2011). This project seeks to find ways to enhance the positive relationship between livestock production and the maintenance of small wetlands. Of course, some wetlands are on public lands and small properties not used for production, and the project also works with the managers and owners of these lands.

Works Cited

Ferranto, P., Huntsinger, L., Getz, C., Nakamura, G., Stewart, W., Drill, S., Valachovic, Y., DeLasaux, M., Kelly, M. 2011. Forest and rangeland owners value land for natural amenities and as financial investment. California Agriculture65(4): 184-191.

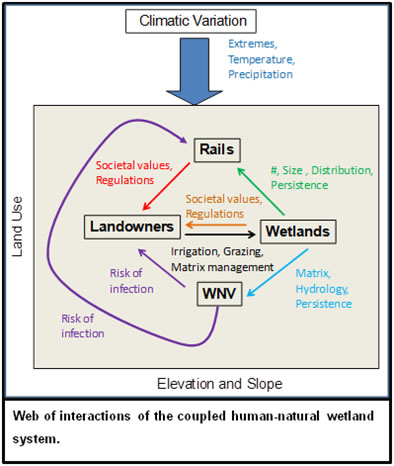

The stewardship of landowners and managers is critical to the sustainability of small emergent wetlands in the foothills. The project will interview and survey landowners and managers to determine what values, if any, landowners may find in the wetlands, and whether or not they are managing the wetlands for any particular purpose. We are particularly interested in how water costs, changes in land use, and concerns about West Nile Virus might influence wetland management.

You can help us by sending your questions and concerns. You can contact the Wetland Project through e-mail under the Contact Us section.

Rails (Family: Rallidae) have a life history that is intimately tied to water. With large, strong feet and shorter, stubbier wings, rails prefer to swim or walk on water-saturated ground than fly. They are most commonly found in dense vegetation near lakes, rivers, and marshes making them difficult to observe and difficult to study. In fact, little is known about their ecology and behavior. With a decline in wetlands in California, there is believed to be a decline in populations of such wetland-dependent birds such as the state-threatened California Black Rail (Laterallus jamaicensis coturniculus; Black Rail) and the more common Virginia Rail (Rallus limicola).

Both Black Rails and Virginia Rails are found, often together, in the smaller, more fragmented wetlands in the Sierra Nevada Foothills. This patchy distribution of wetlands creates a patchy distribution of rails. This type of distribution is called a metapopulation, a large population composed of several smaller populations. In metapopulations, birds that occupy a wetland one year may not occupy it the following year. This is called an extinction event. Similarly, birds may be absent from a patch of wetland one year, but they may inhabit the same patch of wetland the next year in a process called colonization. As a result, every wetland is vital to the maintenance of the metapopulation structure of Black Rails and Virginia Rails in the foothills.

The California Black Rail, a distinct subspecies of the Black Rail, is a poorly understood wetland bird that is restricted to the Western United States. The California Black Rail is the smallest rail in North America comparable to the size of a sparrow. This small bird is usually concealed in in thick vegetation and will usually only make its presence known by its unique calls. The distribution of the Black Rail resembles the distribution of Californian wetland habitat in its fragmentation. The majority of the population resides in tidal marshes of the San Francisco/Bay Area. Along with a few freshwater wetlands in Arizona and Southeastern California, palustrine emergent wetlands in the Sierra Nevada foothills are considered home to a small, unique population of California Black Rails.

The origin and movements of this recently discovered population are unknown. As opposed to the Eastern subspecies of Black Rail, the California Black Rail is not known to migrate making long-distance dispersal highly unlikely among individuals in the foothills. Movement between patches is presumably at a local scale. As a result, changes to the wetlands may equate to changes in the Black Rail population in the foothills. By using occupancy surveys, the Wetland Project aims to monitor the movements of this state-threatened species in response to habitat availability and to presence of other wetland threats such as West Nile Virus.

In addition to California Black Rails, freshwater wetlands in the Sierra Nevada foothills support a breeding population of the more common Virginia Rail. These rails are about three times larger in size than California Black Rails and are capable of flying much longer distances. This dispersal ability has helped the Virginia Rail become a widespread and common rail species in North America. While they are larger in size with respect to the Black Rail, Virginia Rails possess the typical “thin-as-a-rail” bodytype that allows them to move easily through dense vegetation. Their physical attributes and greater tendency to fly from danger make them more likely to be seen, but they remain one of the more secretive birds in North America. As with the Black Rails, Virginia Rails populations are dependent on the surrounding wetlands that are available to be occupied. By looking at the presence and absence of Virginia Rails in wetlands, The Wetland Project will observe how patterns and changes in wetland characteristics affect the distribution of Virginia Rails.

Due to their secretive nature, Black Rails and Virginia Rails are often identified by their distinct vocalizations. Next time you’re near a wetland, you may be lucky enough to hear one calling!

Black Rail ki ki krr Song

Black Rail Growl Call

Virginia Rail Grunt Call

Virginia Rail Tick-it Song

West Nile Virus (WNV) arrived in California four years after its first introduction in 1999 and has been repeatedly transmitted every year. Mosquitoes, in particular the species Culex tarsalis in the western United States, are primarily responsible for the transmission of WNV in non-urban areas. Mosquitoes prefer breeding in stagnant or slow-flowing water. The arid and warm summer months in the Sierra Nevada Foothills leave the landscape dry except for irrigation ditches and wetlands. As a result, the presence and abundance of mosquitoes in the area are not only related to their predators and their competitors, but are also closely linked to the water quality and the size and persistence of wetlands.

In the summer of 2005, WNV appeared in the mosquitoes of the Sierra Nevada Foothills and presumably used many birds including Black Rails and Virginia Rails as hosts. WNV infected a large number of mosquitoes in Yuba County the year after its introduction. In 2007 and 2009, annual surveys for Black Rails and Virginia Rails yielded surprising results. Both species were not detected in many of the wetlands that they previously occupied. Tests confirmed that WNV had infected some rails, but more information is needed to draw any further conclusions. By tracking the transmission of WNV in rails and mosquitoes, we can begin to understand the impacts of WNV on the persistence of birds in wetlands.

Natural wetland systems are highly sensitive to fluctuations in temperature and precipitation. The global mean increase of more than 1ºC since the 1880s is observed in the recent Sierra Nevada snowmelt that occurs more than 20 days earlier than in the 1950s. Future climate projections suggest an average of 1-4ºC increase in the global mean temperature over the next 40 years. This could influence the likelihood of heavy precipitation, flooding, and drought events. The increased evaporation may water lower tables year to year and decrease the extent of current wetlands making smaller, more fragmented wetlands. In the Sierra Nevada foothills where the natural wetlands are already fragmented and small in comparison to many coastal wetlands, this could mean the disappearance of many wetlands that benefit us all.